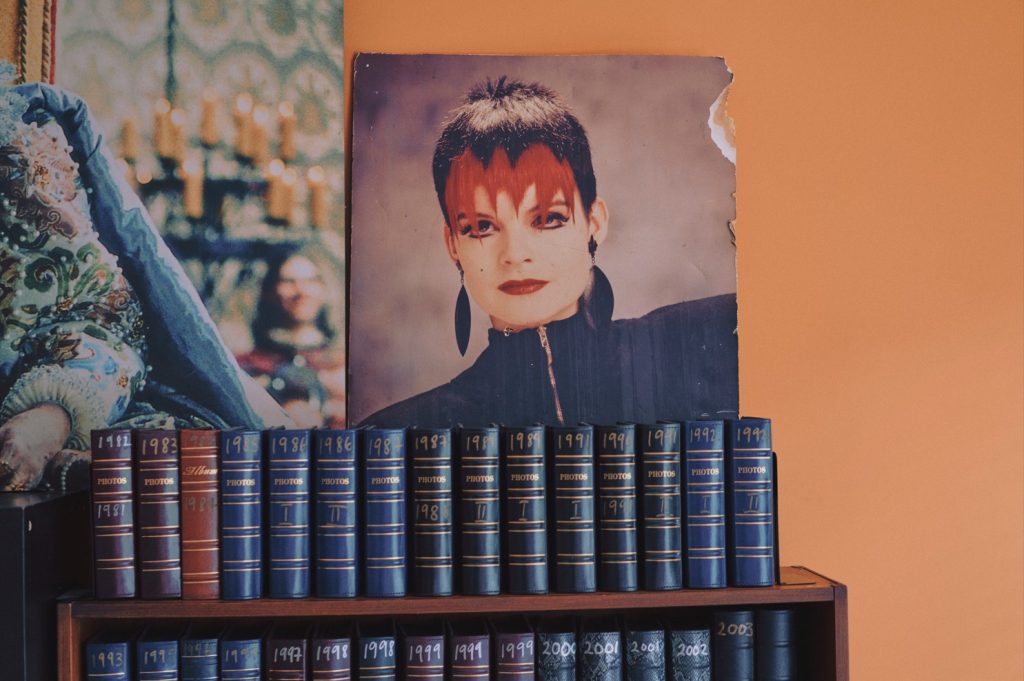

Cutler and Gross’ In Conversation series celebrates the brand’s customers and their personal style. We look closer at their work and how they ended up in their individual creative field, what their specific craft looks like and what their creative process is. The series continues with award-winning Costume Designer Sandy Powell.

Interview and Art Direction David Hellqvist – Document Studios | Photography Tom Jamieson

We all know it takes a lot of hardworking people make a Hollywood feature film happen. Usually, it’s the director and lead actors who have most of the screen time and media presence but if you hang around for the credits you’ll add 10 minutes to the film, that’s how many professionals have a helping hand in the making a box office hit, and among cinema’s unsung heroes the costume designer is the film’s visual vanguard.

Case in point: Sandy Powell. The award-winning costume designer has worked on seven films with Martin Scorsese and won three Oscars and three Baftas for her visual work spanning three and half decades. But Powell’s first few steps in the film industry were arguably as impressive as her latest films, including the ‘The Irishman’ with Scorsese and the Disney blockbuster she is currently working on. In the early 80s, Powell – through a mixture of luck, confidence, and talent – met and started working with the legendary British arthouse director Derek Jarman. Powell collaborated with Jarman on some of his most influential films, such as ‘Caravaggio’ (Powell’s first ever film project!) and ‘The Last of England’.

This working relationship helped build Powell’s reputation for alternative and off-piste period dramas, full of strong characters needing impactful costumes. When Scorsese came knocking for the 2002 release of ‘Gangs of New York’ this was Powell’s ticket to a whole new global Hollywood stage. But in-between, Powell had also started working director Todd Haynes, another one of her long-term professional partnerships, which led to Powell to do ‘Velvet Goldmine’ in 1998, for which she won a BAFTA. So, Powell’s own tale is one of big films, powerful names and lots of awards and accolades. But at the core it’s a story of a strong creative mind with a knife-sharp aesthetic and an eye for iconic movie costumes. Perhaps worthy of a film in itself?

Where does your interest in clothes and costumes come from?

From a very young age I was interested in clothes, and I guess it started with me making clothes for my dolls. I was born in 1960 and back then people made their own clothes, so my mother would make clothes for myself and my sister. She taught me to sew, and I started with doll clothes. And then soon after that I had a go at making things for myself. I cut something of hers up and tried to turn it into something for myself. I was maybe 10 or 11.

Do you still make your own clothes?

No, I wish I did but I don’t have time. But I can still do things if I have to, I have done jobs where I’ve had to get in there and do some alterations at the last minute. The most useful thing about knowing how to sew is it helps with my job as a designer because then I can work closer with the pattern cutters and makers, and I think it’s absolutely essential if you want to be a costume designer that you have the know-how to do it yourself.

When you did your foundation course at St. Martins, were you thinking of going into fashion?

No, I wasn’t actually. I’ve always enjoyed fashion, but even before the foundation course I got a real love of theatre through seeing stage performances, especially by a company called the Lindsay Kemp Company. Visually I’d never seen anything like it, and I was just like ‘Wow, this is exciting’. The whole experience of theatre and live performances excited me. The visuals on stage and the transformations, that was the world I wanted to be part of. I didn’t really think about costume design in particular, but that was the world that interested me.

“I asked university for a year off, but I never went back. I had failed school anyway because I had done very little work and a lot of partying”

So, what was your road into costume design from there?

I think it might have been my tutor at St. Martins who encouraged me to look at doing theatre design as a career. And so that’s what I did, went to Central and studied it for two years, which involved designing sets as well as costumes. I dropped out because I met Lindsay Kemp, who I mentioned before, and he offered me a job. I asked Uni for a year off, but I never went back. I had failed school anyway because I had done very little work and a lot of partying, haha.

How did you end up meeting and working with Derek Jarman?

While I was working with Lindsay Kemp, I hooked up with some people who ran a small fringe theatre company called Rational Theatre. I did a bunch of shows for them over a couple of years, designing the sets and the costumes and we worked mostly at the ICA. I’d seen a few of Derek’s films – like ‘Jubilee’, ‘Sebastiane’ and ‘The Tempest’ – and I was thinking it would be interesting to go into film, so I randomly got hold of his number, called him up and asked him to come to see this show at the ICA that I’d designed. He came by and then that was that!

Wow. You ended up working with him on several films, and have longstanding relationships with the likes of Martin Scorsese and Todd Haynes – what do you look for in a director?

The directors I enjoy working with are the ones who are visual, which sounds really strange because obviously all directors are visual, but some communicate it differently and better than others. Derek was a designer and a painter, so he came from fine art, he also did set and costume design, so he completely understood that world. There are many directors who come at it from a completely different point of view, maybe they are writers, and they don’t understand the design process in the same way. There are directors who leave it up to their designers to provide them with everything, which is fine, but it’s much more exciting to be working with somebody who you can bounce ideas off.

“For Cate Blanchett’s character [in 2015’s Cinderella] I was looking at the 1940s, and for the ugly sisters I was looking at the 1950s, so I was doing a 1940s and 1950s version of 18th and 19th century as a sort of homage to the original film which came out in 1950. That was good fun.”

How important is historic accuracy for you, is that sometimes the most difficult part of it?

It’s impossible to be completely historically accurate in a film as most of the time we weren’t there when it happened in real life. But also, the fabrics of today and the machines used to make the clothes are different so it will never be exactly the same. But we’re not making pieces for a museum, we’re making pieces for entertainment, so I think that’s fine. There are plenty of films where the director wants it to just have an essence of the period, which makes it more of a timeless film. For example, people thought Derek’s ‘Caravaggio’ was a period film, but it absolutely was not: it was kind of set in the 1940s and inspired by the Italian neorealist films of that time.

How do you research a period drama?

You look at portraiture, paintings and written material. You read a lot of descriptions of things, like in people’s diaries. After that I go broader, I look at contemporary fashion, I look at fashion from all periods, because that’s always interesting. ‘Cinderella’ was set vaguely in the 18th or 19th century but for Cate Blanchett’s character I was looking at the 1940s, and for the ugly sisters I was looking at the 1950s, so I was doing a 1940s and 1950s version of 18th and 19th century as a sort of homage to the original film which came out in 1950. That was good fun, I enjoy mixing it all up like that.

And is there a difference if the film is about a real person who has lived, or is alive, as opposed to fictional characters?

Yes, if we’re doing a project about a real moment in time, or about a real person, you want to be as accurate as possible. For example, Scorsese’s ‘The Aviator’ was about real people where Leo [DiCaprio] was Howard Hughes and Cate Blanchett was Kate Hepburn … there were a few costumes where I actually copied what they were wearing, and then the rest I just gave them an essence. I designed my version of a Katharine Hepburn look, and that’s how you do it.

What is the process like when creating an outfit for a principal actor, is it much like a designer sketching out a garment?

Yeah, it’s the same thing. You design something from scratch, choose the fabrics, talk to the cutters and the makers, and then you make a version of it, like a toile, then you go into the real fabric. I rarely start with a sketch though, I usually start with a fabric and when I do a sketch it’s for the cutter or maker, never the director or actor because they wouldn’t understand a technical drawing. The fabric will lead me to what the silhouette and shape is going to be. It’s very organic so we do a trial run ourselves first and then, during the fitting, is when the designing actually happens. I need to work in 3D on the person because it’s not like fashion where you’re just making an item of clothing to go on a person, whether or not it suits them … it’s about making something that works for that body, for that specific person playing that specific role.

And I suppose it’s not like they just need one or two outfits, some of these films are two hours long.

In ‘The Irishman’ Robert De Niro had at least 50 changes. It might have been more actually – I’m bad with remembering numbers like that. But then there’s other ones, like the film I’m doing currently, ‘Snow White’, and she’s only got … No, I’d better not say, but it’s very few looks. I treat fairy tale films like children’s picture books where the main characters wear the same thing all the way through so that the kids know who they are throughout the film. But then you get stories like ‘The Irishman’ which is set over several decades, and then within those decades, years, months, weeks and days they’ve got to keep changing their clothes so that we know that the time is moving.

If you like the frames Sandy is wearing but you’re not sure how round frames would work for you, refer to our Face Shape Guide for guidance. Though it’s worth noting, there are no hard and fast rules in choosing eyewear that you’ll love.

Read our journal on the Return of Round Glasses and our Design Essay on the King of round glasses and our SS/22 Muse, David Hockney.