Julius Shulman is celebrated as a titan of architectural photography. During his prolific 70-year career, the Brooklyn-born lensman worked with some of the most significant names in architecture and design, including Richard Neutra, and Charles and Ray Eames.

Shulman’s career took off in the 1930s, coinciding with the emergence of Modernist architecture in America. His images were pivotal in popularising the movement and shaping its enduring legacy. Cutler and Gross’s Spring Summer 2024 collection – Desert Playground – is an ode to his pioneering vision.

Here, we delve into Julius Shulman’s expansive career and discuss two iconic photographs.

“I was lucky to be doing the right thing in the right place at the right time” is how Julius Shulman self-deprecatingly described his career beginnings to the Los Angeles Times. In 1936, having failed to graduate with a degree in electrical engineering from the University of California, Berkeley, he went to visit his sister in Los Angeles. She had a lodger at the time, a draughtsman working on architect Richard Neutra’s nearby property, who invited Shulman to see it.

Shulman went with his Kodak pocket camera and took a series of 8×10 photographs. According to journalist John Grace, Neutra was so impressed by the images that he ordered 6 of each. From there began a collaborative relationship that spanned decades of properties and projects, as Neutra introduced the self-taught photographer to other architects working in California at the time. Shulman’s baptism into the world of architectural photography had begun.

A home-grown aesthetic, Desert Modernism first emerged in Palm Springs, California in the 1930s. It drew inspiration from the strict geometry of the European International Style and the Bauhaus, adapting them to suit the Californian climate.

Indoor-outdoor living was a central tenant of the movement, characterised by floor-to-ceiling glass walls and sliding doors. It advocated a clean-cut aesthetic, with flat roofs and industrial steel components, while airy floor plans, slats and swimming pools kept temperatures cool.

Constructed between 1946 and 1947, Richard Neutra’s Kaufmann Desert House in Palm Springs helped spearhead the aesthetic. And Julius Shulman’s resulting images cemented its iconic status.

By 1937, American businessman Edgar J. Kaufmann had already commissioned an iconic masterpiece of modern architecture: Frank Lloyd Wright’s ‘Fallingwater’, a Tetris-like structure balanced above a stream in the Appalachian Mountains.

Nine years later, Kaufmann acquired 2.6 acres of land at the base of Mount San Jacinto in Palm Springs and commissioned Neutra to build him a holiday home. The subsequent Kaufmann Desert House has a pinwheel-like structure – a Neutra signature – that extends from the centre of the property out into the desert. A deliberate antithesis to Lloyd Wright’s ‘Fallingwater’, which seamlessly integrates with its surroundings, Neutra juxtaposed a horizontal roof, polished glass, and steel beams with the craggy mountains above.

Shulman first shot the Kaufmann House upon its completion and then returned to it repeatedly throughout his career. Predominately photographed in black and white from a single-point perspective, Shulman’s images emphasise the dramatic, pioneering contrast between building and landscape.

Over the next forty years, the Kaufmann House was passed down through a series of owners, one of which was Nelda Linsk. It was during her tenure that Slim Aarons’s iconic ‘Poolside Gossip’ photograph took place; we spoke to Linsk about the story behind the lens here.

With each new owner the property changed, extensions were added and removed, wallpaper plastered and stripped off. In the 90s it fell into disrepair, eventually being put on the market as a plot of land with the property listed as a tear-down.

The Kaufmann House was bought by architectural historian Beth Harris and her husband Brent, who were determined to restore it to Neutra’s original aesthetic. The Los Angeles architectural firm that received the commission described Julius Shulman’s imagery – which was pivotal in establishing the property’s legacy – as an ‘invaluable source’ of information to restore it.

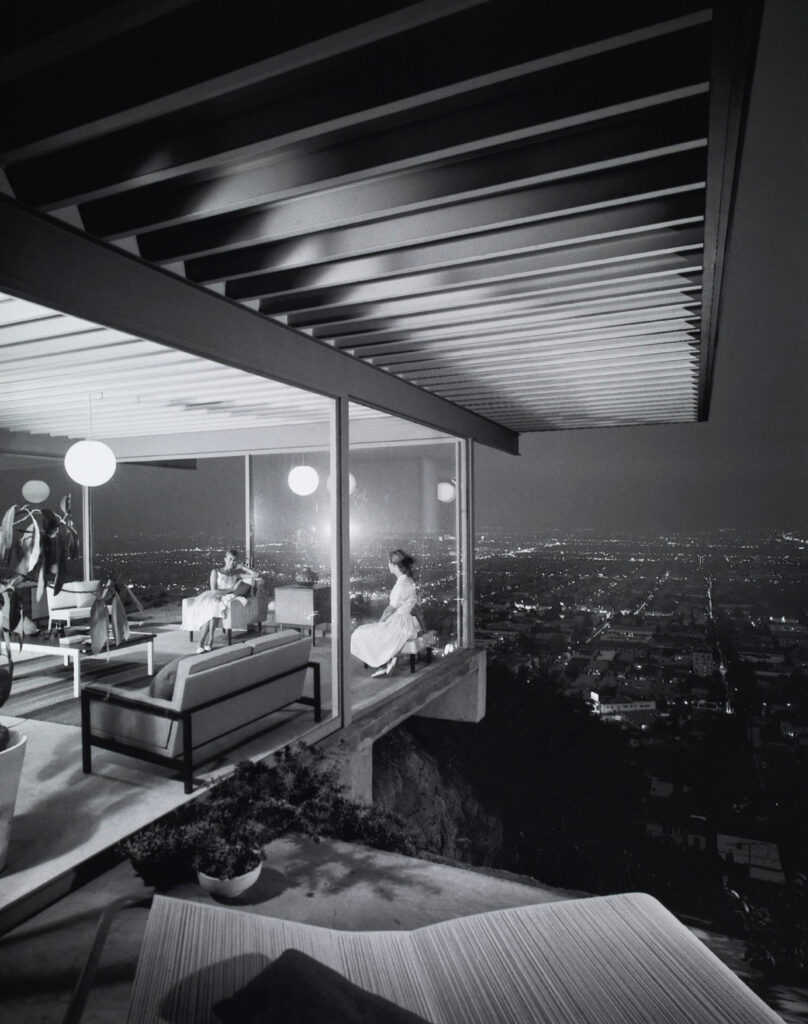

The Kaufmann House photographs helped propel Shulman’s career; the Case Study House #22 images cemented it, positioning him as the pre-eminent architectural photographer.

The property was part of a program established in 1945 to help solve the post-WWII housing shortage and bring Modernism to the masses. Designed by Pierre Koenig, the residence resembles a glass box perched above Los Angeles. Shulman’s subsequent photograph was described by TIME magazine as “one of the most important images of all time”.

Taken at night, two elegant women in cocktail dresses are depicted in relaxed conversation in the corner of the building, while the cityscape glows below. Shulman’s composition didn’t simply freeze the structure in the frame, it captured a sense of optimism and prosperity in the post-war landscape. Koenig’s architectural experiment became a symbol of modernity.

Julius Shulman contributed immeasurably to the discourse of Modern architecture. His photographs mythologised the buildings and acted as an invaluable record of both a movement and an era. In acknowledgement of this, he was granted an honorary lifetime membership of the American Institute of Architects.

In 2005, Shulman gifted his monumental portfolio to the Getty Research Institute in Los Angeles. The archive now houses over 260,000 negatives, prints and colour slides of Shulman’s work, a testament to a man who transformed architectural photography into fine art.

Julius Shulman’s photographs of Desert Modernism in Palm Springs laid the foundations for the latest collection of Cutler and Gross glasses and Cutler and Gross sunglasses. The inimitable designs draw inspiration from the experimental architecture of this bygone era, captured in Shulman’s frames.

Available online and in-store now.