On 3rd July 1947, 4,000 motorcyclists descended onto Hollister, California. With a population of only 4,500 and a seven-man police force, the town was overwhelmed. For three days, a rampage of bikers drove, drunk and slept on the streets. Immortalised in LIFE magazine, the events that occurred became the catalyst for the Outlaw Biker – a petrol-fuelled, chaos-causing trope that inspired the latest Cutler and Gross X The Great Frog collaboration.

However, the ‘Hollister Riot’, as it was dubbed, was perhaps not all that it seemed. From post-World War II veteran adventures to the birth of the ‘One-Percenters’, we chart the myth and might of the Outlaw Biker.

The Military Motorcycle Boom

Over the course of WWII, Harley-Davidson, Inc. supplied more than 90,000 motorcycles to the US armed forces. Thousands of serving soldiers learnt to ride during the war effort, returning home on their army surplus machines. Motorcycling clubs swelled in popularity, providing veterans with a much-sought-after sense of brotherhood, adventure, and adrenaline.

Pre-war, the biker community was a tamer type. Since the 1930s, the town of Hollister had hosted the annual American Motorcycle Association (AMA) Gypsy Tour rally, a social three-day event where approximately 1,000 riders would participate in organised hill climbs and field games such as tug-of-war and barrel racing.

Halted during the war, the Gypsy Tour returned to the rally calendar in 1947 and the number of attendees had quadrupled. The small town was overwhelmed, unable and unprepared to house or cater for the motorheads, who arrived in their thousands.

Bikers dragged-raced through the streets, which were littered with bottles and sleeping bodies. Fuelled by alcohol, scuffles broke out. The local bars, which had initially welcomed the influx of customers, closed early. Hollister’s seven-man police force was unable to handle the numbers so called in the state police.

Reportedly, most bikers – veterans accustomed to obeying authority – cooperated and took the party out of town. The chaos wound down, bikers drifted off in search of other destinations, and the town slowly returned to normal.

Hollister Riot or Rally?

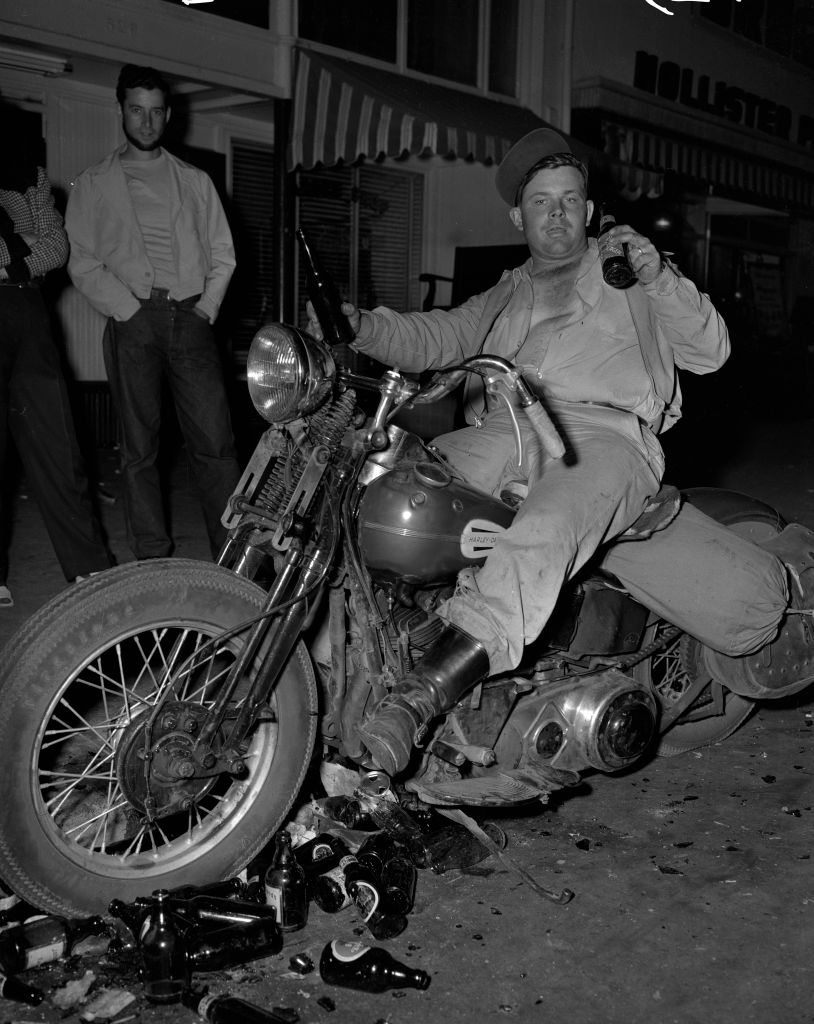

Some argue that the event was then sensationalised by the press, dramatized most acutely in an image published in LIFE magazine.

Captured by photographer Barney Peterson, a drunken-eyed man reclines on a motorbike, alcohol in hand, surrounded by a sea of discarded bottles. It was accompanied by the headline: “Cyclist’s Holiday: He and Friends Terrorize Town”. With a cross-continent readership of nearly five million, the LIFE magazine article was damning. The image is widely considered to be the origin of the ‘outlaw biker’ trope, painting a picture of dangerous, speed-hungry mavericks that cause carnage and disrespect the law.

However, the photograph was reportedly staged. It is alleged that eyewitnesses saw Peterson gathering bottles before positioning the bike in amongst the pile. Fact or fiction, it immortalised the idea of the rebel motorcyclist in the cultural consciousness.

One-Percenters

In response to the LIFE magazine article, the AMA released a statement with the aim of distancing itself from this newly formed ‘outlaw’ image. They wrote that 99% of their members were law-abiding citizens, and only 1% were outlaws. The term the ‘One-Percenters’ was born, and rebel bikers embraced it.

The events at Hollister and the subsequent media coverage shifted the dialogue around the motorcycle community. It splintered into two groups, those recognised by the AMA, and the One-Percenters, who were not. Bikers donned their cut jackets and attached patches that pledged allegiance to their crew. The likes of the Hell’s Angels formed, adopting the One-Percenter label like a badge of honour, using it to define and harden their identity.

From Hollister to Hollywood

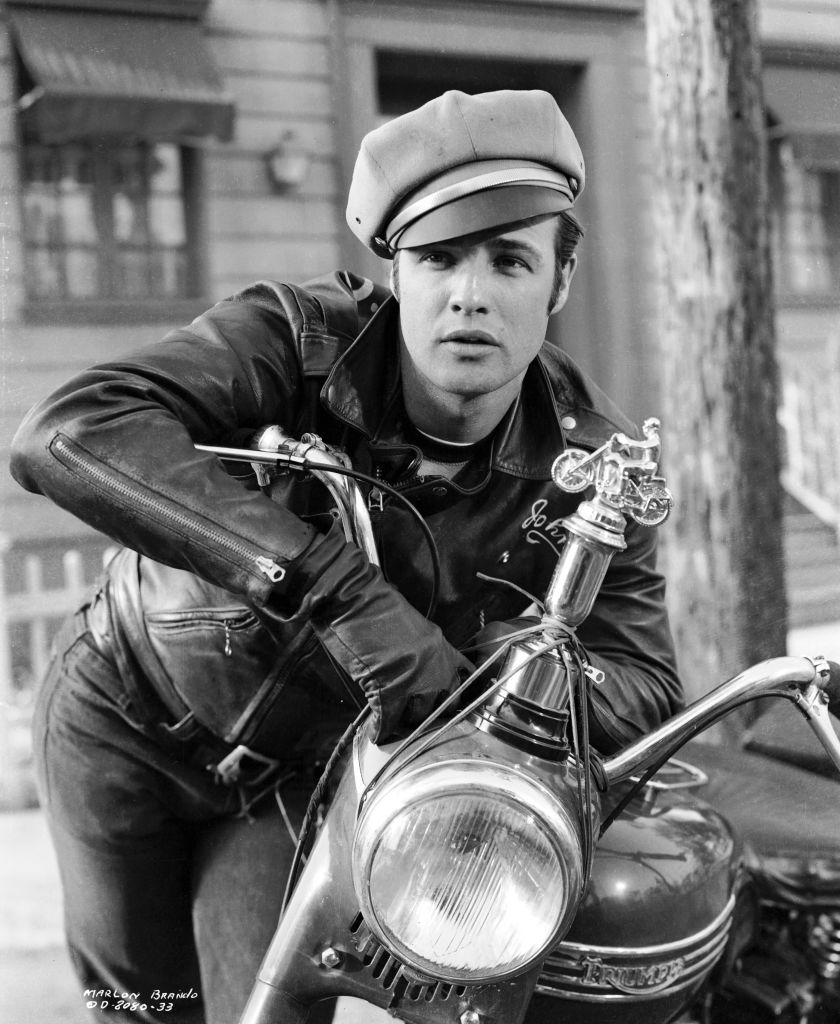

László Benedek’s 1953 classic ‘The Wild One’ was directly inspired by the 1947 Hollister riot. Marlon Brando portrayed the protagonist, gang leader, and now cultural icon – Johnny Strabler. Considered to be the first of its kind, the film spawned an entire genre around outlaw bikers. It was also one of the most controversial movies of its time.

A seismic shift in society took place during the 1950s. Post-war, post-rationing – the Baby Boom and increased affluence created a melting pot for a new youth culture. The younger generation began to challenge social norms and rebel against their parent’s values. Soundtracked by rock’n’roll music, the Generation Gap formed.

Clad in leather and denim, a brooding Brando was the poster boy for disaffected youths. In one iconic scene from ‘The Wild One’, his character is asked, “What are you rebelling against, Johnny?”, to which he nonchalantly drawls, “Whaddaya got?”. In those four slurring syllables, he succinctly summarised the generational desire to challenge the status quo.

As a result, the BBFC (British Board of Film Classification) banned the film almost immediately after it was released, stating that it portrayed ‘a spectacle of unbridled hooliganism’. The censorship remained until 1967, when the BBFC released it with an X rating.

Rock Rebellion

The image of the Outlaw Biker has remained central in the imagination of Reino Lehtonen-Riley, The Great Frog’s creative director. As a young boy he would sit cross-legged in front of the TV, enthralled by the likes of Marlon Brando and Peter Fonda, and dream of switching his battered BMX for a petrol chrome machine.

Reino’s renegade roots and The Great Frog’s authentic links to hard rock counterculture laid the groundwork for the new collection of sunglasses and opticals. From subversive cat-eyes to statement squares, explore the latest Cutler and Gross X The Great Frog collection now.